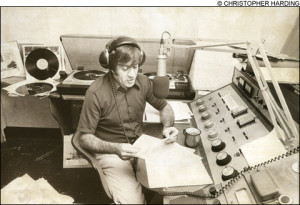

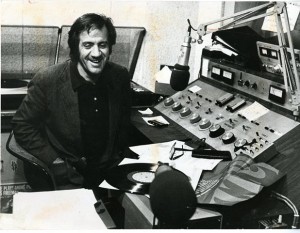

I was going through some old tapes and found a late-night interview I did in the ’80’s with Tony Cennamo, the legendary WBUR Boston DJ.

Nothing I can say about him wasn’t said better by his WBUR colleague, Steve Ellman, in a moving memoriam written at the time of Cennamo’s passing in 2010 at the age of 76.

You can read Ellman’s tribute here.

Tony was ebullient and full of life, despite a few strokes and a careful adherence to sobriety. I’ll never forget him bursting into the rather sedate bar at a high end hotel in Bermuda where I was doing a solo show, shouting, ‘I heard Anne Farnsworth was playing here!’

Here’s our interview, minus the music selections. Those are posted on my YouTube channel, Anne Farnsworth Music.

Boston.com columnist Roy Greene, among many others, also published a remembrance at the time. They include many of Tony’s often hilarious, decidedly un-pc opinions; fightin’ words from the big hearted man who lived and breathed jazz:

“Brooklyn accent riffing through the Boston night, Tony Cennamo used his expansive understanding of jazz as a counterpoint to the records he played past midnight on WBUR FM, entertaining and educating sleepless lovers of everything from bebop to avant-garde.

Listeners can hear his voice speaking the words he wrote for the Christian Science Monitor when he took a moment “to vent in print what is on the tip of my candid tongue” in January 1985. Musicians’ names cascaded like a soaring saxophone solo.

“Jazz is Monk, Ornette, Duke, Bird, Dizzy, Miles, Trane, Toshiko, Pee Wee Russell,and Gil Evans, Mingus the imaginative, the juices flowing, not the bland, watered down, the whitewash of a thousand Xeroxed copies,” he wrote. “Jazz is not safe and doesn’t hide in Symphony Hall.”

He didn’t play it safe, either, and his precisely rendered opinions helped shape jazz tastes for a generation of fans during the quarter century he spent on WBUR. Mr. Cennamo, who also taught at Emerson College for many years, died Tuesday in Glen Ridge Nursing Care Center in Malden. He was 76 and had suffered a seizure in April.

“Tony’s the rare thing that most disc jockeys are not,” vibraphonist Gary Burton told the Globe in 1987 as he and others prepared a tribute concert to honor Mr. Cennamo’s then-15 years of spinning jazz records on WBUR. “He’s also a musician, a trombonist, which makes him a better DJ. It comes out a lot in his interviews. He doesn’t sound like a fan interviewing a star. He’s a real champion of the new musician in town and his interest extends beyond the currently popular to the future of music.”

When Mr. Cennamo left WBUR in 1997, Globe jazz critic Bob Blumenthal called him “Boston’s most constant jazz voice,” someone whose “deep knowledge of the music and broad taste made his programs invaluable resources for listeners.”

Mr. Cennamo, who was master of ceremonies for the Boston Globe Jazz Festival in years past, kept an eye on the past and present, too. Steeped in the genre’s history, he would tell anyone who asked, and many who didn’t, that jazz was an African-American art form.

“Most new forms of jazz music are initiated by black musicians,” he wrote in the 1985 Monitor article. “White players (with few exceptions) copy, black musicians invent!”

He also looked askance at soothing new age music and the artists featured on the Windham Hill recording label, rejecting the suggestion that jazz could be found in, say, the piano playing of George Winston.

“Cheers for those club owners and bookers who stick out their financial necks weekly to bring us some of the most talented players in jazz,” he wrote. “Meanwhile, George Winston fills Symphony Hall with his nonjazz, nonrhythm, lukewarm, Jacuzzi-inspired piano offerings.”

James Isaacs, a former Boston Phoenix writer who became a colleague on the air at WBUR, said that even when discussing musicians he admired, Mr. Cennamo employed a ready sense of humor to humanize performers that many place on a pedestal.

“People who broadcast jazz on the radio treat it with such reverence,” Isaacs said. “Cennamo always had a sense of reality, and there was a certain sense of outrageousness about him that I always found attractive. It wasn’t, ‘Now, ladies and gentlemen, the great Zoots Sims, the great John Coltrane.’ No, they were just musicians.”

The oldest of three children, Mr. Cennamo grew up in Brooklyn, N.Y. He told the Boston Herald Sunday Magazine in 1987 that the first record he bought was a collection of Duke Ellington tunes, chosen because of the trombonist, Lawrence Brown.

“I listened to jazz in my room at night,” he told the Herald. “I loved it so much, my parents thought I was crazy.”

He joined the Air Force and was stationed in Omaha, where he formed an integrated jazz ensemble and railed against any club owner who tried to exclude the band because it included black musicians.

While in Nebraska, he met and married Doris Steffen, and used the GI Bill to attend Creighton University in Omaha. He got his first experience on radio across the Missouri River in Council Bluffs, Iowa, then moved his wife and children back to Brooklyn, landing a job in the WCBS radio library.

Among his first producing opportunities was a folk show for WCBS, through which he met the likes of Carly Simon, Phil Ochs, and Mary Travers of Peter, Paul, and Mary. He also was a producer of Pat Summerall’s sports show.

“He enjoyed listening to all kinds of music, as long as it was done well,” said his son, James of Arlington. “But he must have heard something that touched his soul in jazz music.”

In 1967, Mr. Cennamo took a job with WCAS AM in Cambridge, where he ran a community talk show that dealt with polarizing topics such as opposition to the Vietnam War.

WBUR offered him a weekly jazz show in 1972, and he moved to weekday mornings in 1974. The disc jockey made cameos in Robert B. Parker’s Spenser mysteries, with the Boston detective listening to his radio show while on the job.

The station revamped its programming in 1981, shifting Mr. Cennamo from mornings to a 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. shift, and edged him ever later over the years until he was signing off at 4 a.m. at the end of his tenure in 1997.

Mr. Cennamo, whose first marriage ended in divorce, augmented his radio work by teaching jazz history and radio programming at Emerson and in other venues.

New to Boston, Carine Kolb met him in 1986 when she took one of his classes. They married three years later.

Mr. Cennamo suffered his first stroke in 1986 and returned a few months later to teaching and the radio show. While the stroke hobbled him physically, it had the unanticipated effect of reinvigorating his approach to work.

“For a while, I was getting tired of radio,” he told the Herald in 1987. “But after the stroke, I’m glad I can do anything. I’m rejuvenated by the time off. I’m ready to explore new programming ideas.”

“He would go to WBUR in the middle of winter, with snow on the ground, with a very strong limp and a cane, still carrying a very big bag of records, because he wouldn’t go anywhere without a stack of records,” his wife said.

Isaacs called Mr. Cennamo “one of the most unforgettable people I’ve ever met. You just don’t come across many guys like that in this life, guys who are unafraid to speak their mind and who do things for other people not expecting anything in return. They just do it, and they’re amusing while doing it.”

(180)